“I am not a fancy cook or an ambitious one,” writes Laurie Colwin in her book of essays and recipes Home Cooking: A Writer in the Kitchen. “I am a plain old cook.”

By the fact of this line having been published in her book of essays and recipes, one can safely say that despite her protestations, she is not a plain old cook. I understand her, though. Those of us who make work of our domestic labors (a very privileged position) often want to be thought of as just simple guides to better, easier, tastier living and not gods ruling from on high about just the right way to make a basic vinaigrette. “You can balance the following ingredients to suit yourself,” she writes in another chapter. It’s your tongue, she seems to say, and I am one-hundred percent on board with this approach. I can provide guidelines but I can’t teach you what you like. You have to trust yourself there, and that’s I think the most important lesson for the home cook.

I have been having the experience of my domestic labor and labor-labor being too much lately, and I have been (perhaps unfairly) blaming my gender. While I was growing up, I did not sit at my mother’s side in the kitchen and learn a goddam thing. I was fed well, and I loved food, but she told me not to learn how to cook because then I’d spend my life cooking for a man. When I finally came to cooking in my twenties (a necessity when I gave up eating animal products), I did so with the intensity and enthusiasm I’d always hoped to bring to literary projects—and I did so as an enthusiast, as I thought a man might, not as care-taking. I had wanted to be a writer of strange fiction, yet what really lit a fire under my ass was baking cake and figuring out how to make a bean-based version of the meaty empanadas my mom had raised me on. We’re over a decade on from that moment now. Food, cooking, and baking gave my life meaning. Simple as that.

I’m a woman, though. Married now. A wife. Food is my thing, my passion—where I feel happiest and most creative, as opposed to when I’m writing, like now, when I feel happy enough and most challenged—as well as my work, and it’s also a necessity, and it also has all these annoying patriarchal connotations. This is no longer pure intellectual pursuit, and I relish that about it while it also makes me uneasy. Who am I if I’m doing domesticity, as work and as an expression of love?

I rarely burn out on cooking, but I do burn out on it, and because it’s all of these things at once—life, love, labor—that collapse of my energy feels like a failure on all fronts. Would I feel this way were I a man? I wonder. I want entitlement to exhaustion; I want to state it firmly, assertively: “I don’t want to cook today.” Instead, I swan about, a bit depressed and endlessly agitated, and push myself until I really can’t cook today because there’s a nagging pain in my back from hours of standing barefoot on tile floor.

Even then, I feel ridiculous. Domestic labor is a tale as old as time, and those who came before us by a century or so never had the ability to say, “Fuck it, let’s order a pizza.” While food slowly but surely became outsourced—no longer was every loaf of bread baked in the house—it also eventually morphed into a site of individual satisfaction, which is where I found it and picked it up, professionalized it.

When you chronicle the domestic, as a food writer, you’re telling everyone your ideals and your failures. Making it all foible and learning experience, though the very act of chronicling, of being able to narrate it, means you’ve got a grip on it. I’m a plain old cook. But I’m also a control freak, and I don’t want to eat a mediocre meal for the sake of taking it easy. Herein lies the rub!

I love Rachel Cusk’s essay “Making House: Notes on Domesticity,” because she sees the way the domestic life is a zero-sum game for a woman: You’re defined by partaking as well as rejecting.

The suburban housewife with her Valium and her compulsive, doomed perfectionism has been the butt of a decades-long cultural joke. Yet there are other imperatives that bedevil the contemporary heirs of traditional female identity, for whom insouciance in the face of the domestic can seem a sort of political requirement, as though by ceasing to care about our homes we could prove our lack of triviality, our busyness, our equality.

God, and this part:

The artist in me wanted to disdain the material world, while the woman couldn’t: In my fantasy of the orderly writer’s room I would have to serve myself, be my own devoted housewife. It would require two identities, two consciousnesses, two sets of minutes and hours.

When I was watching the HBO Max show Julia to write about it for Gawker, I found myself wondering to whom she was really a hero for freeing from the tyranny of meatloaf and frozen foods. As writer John Birdsall explained in a Twitter thread, the french omelet of episode one was an obsession for well-to-do women. What about everyone else? The ones who couldn’t send away for the proper pan from Williams-Sonoma? What were they cooking and eating? Did they enjoy the work? Would they have called it work? When can domesticity simply be life, for whom?

In the documentary Julia, there are clips of her talking about her love for men, her love for feeding her husband. Was that performance? If anyone ever asks me, could I reply without irony? Can I ever decouple my cooking from care again? Would I want to—what would it give me if I could?

I mean: Does all food media exist to keep mainly women inspired around what is actually a dull task that needs to be suffused with novelty? Would I love to cook if I’d come to it out of duty rather than desire?

The uproariously funny The Taste of America by John L. and Karen Hess has a chapter on cookbooks that really tears into American women who aren’t curious about cooking—who want things quick, easy, extremely American-ized—and how that was capitalized upon by publishers and editors. I mean, it’s funny to me, but I don’t really think everyone has to care about food. Most people, probably, do not, and there is enough on people’s plates (so to speak) without project cooking or dinner parties being regarded as moral hygiene.

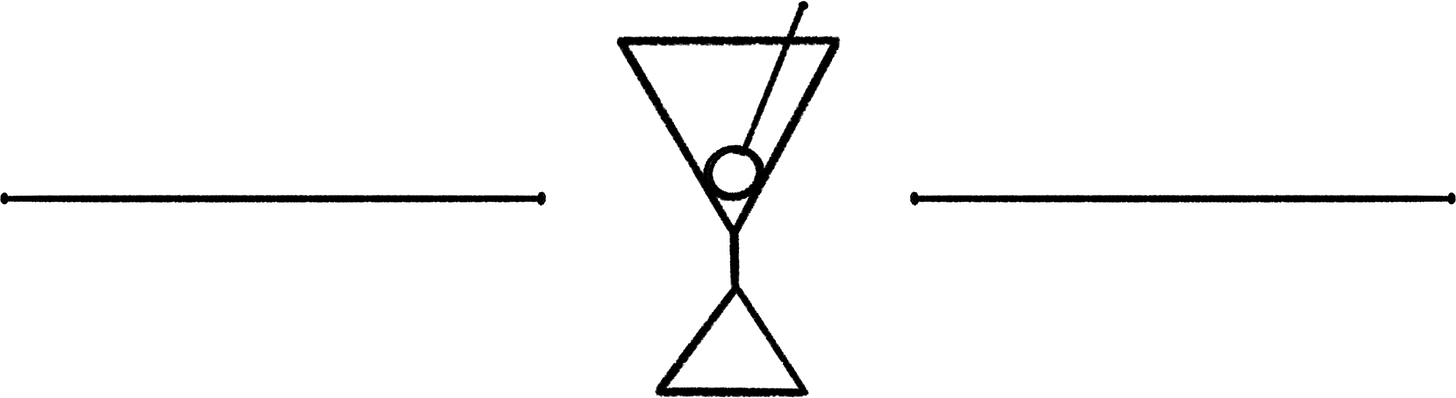

Domesticity is a luxury. I work from home, for myself: I get to dawdle over a pot of beans, mix up tortilla dough, and mop during my downtime. When my husband gets home, I often ask him to make a martini for me to sip on while I cook. It’s all a beautiful little fantasy, until sometimes it isn’t. Until I no longer wish to have a mental inventory of the pantry and the fridge, to always know when we need garlic before we’re out. This mood tends to strike when I have had an especially arduous week of writing or editing work, or when I’ve done five Zooms on different topics—that’s when getting into the kitchen makes me want to cry. This is a burden I’ve placed upon myself, though, because I made love and labor one.

What makes me lucky and grateful is that I’ve learned to see it coming: When the domestic goddess morphs into a domestic beast, I just have to give myself some space from the kitchen and let my husband cook. Inevitably, I wake up the next day gasping for air, struck by a new recipe idea, eager to throw on my apron and sweat in front of the stove. To be a plain old cook, with a wink. To assume the work of care, and make a nice job of it. Food, my love; food, my labor.

Note: In this piece, I set my terms on domesticity—had to get it off my chest! In a future piece, I will be taking a broader, more systemic look at gender and labor in the kitchen.

Last week, I tried to catch people up on the podcast. This week’s episode will feature author Jami Attenberg, discussing her latest book, the memoir I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or adjust your settings to receive an email when it’s out.

Friday’s From the Kitchen dispatch for paid subscribers will include a recipe for guava barbecue sauce to put on mushroom pinchos! An excellent meatless summer dish. See the recipe index for all past recipes available to paid subscribers.

Published:

A conversation with Siobhan Phillips, author of the new novel Benefit, about food writing, kitchen labor, and sugar for Bellevue Literary Press. An interview with Topia.

Reading:

The books mentioned in the above essay, of course, as well as the forthcoming The Undercurrents: A Story of Berlin by Kirsty Bell. I ordered and am really looking forward to books by Lauren Elkin and Caren Beilin. Beilin I am excited about after listening to her on “Between the Covers,” a podcast I’m newly very obsessed with—luckily there are years’ worth of conversations to listen to!

Cooking:

The reason I wrote this essay is that I’m not into cooking at the moment, though I did spend a very good day recipe testing for next week’s pincho recipe, made a lemon-coconut cake with a matcha swirl that I’ll publish soon, and made jackfruit and mushroom tacos. For a friend who got a new job, eggplant parm and a chocolate mousse.

Yes! Yes! Yes! Day to day, at home, I’ve likewise chosen this role and have these moments, but worst when visiting with family and they’ve presumptively determined that I should be the cook for the night—not because this job must be done and we should all share the burden—but because “you love to cook!” I want to scream at them not to tarnish my love this way.

First, I really enjoy your writing. It's snappy and literate at the same time. Second, as a man who cooks a lot, I can tell you that I, too, sometimes do not want to cook. Just order a pizza or get a taco. I am a teacher. Every Sunday I bake bread to take to school and hand out to colleagues and students. Sometimes I just don't feel like it, but I do it anyway because the delight that people have with a simple boule of sourdough or a slice of focaccia is quite rewarding.