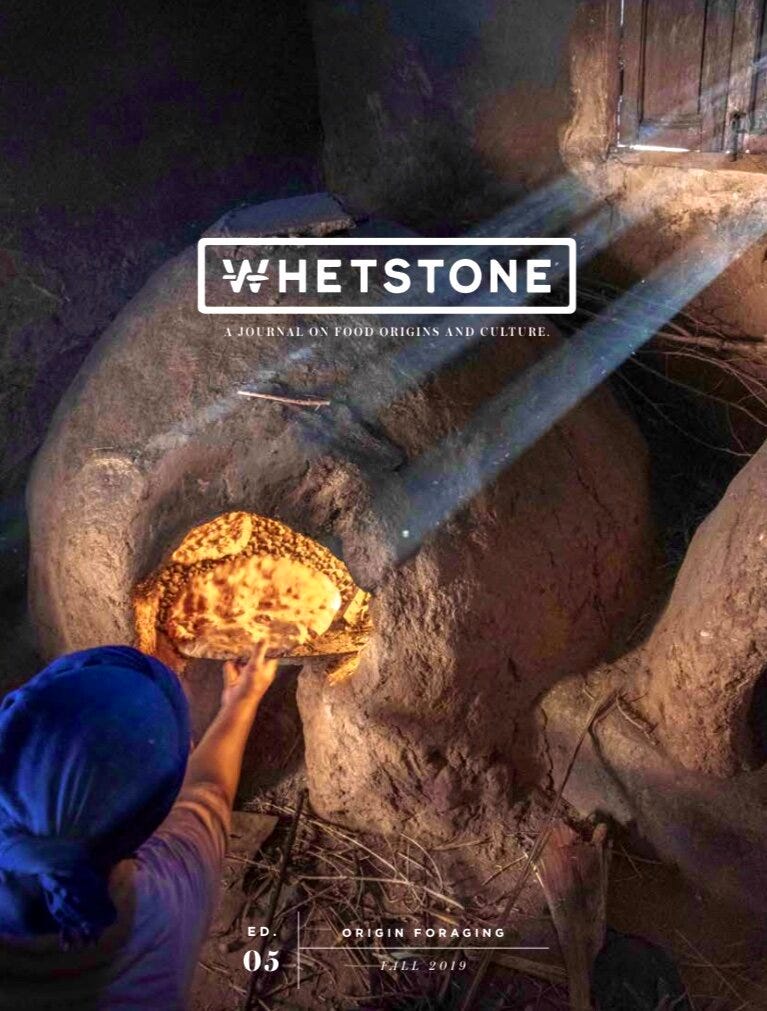

I don’t know how I made it this far without interviewing Stephen Satterfield, whom I’ve known and admired for a few years now. He launched Whetstone magazine, which has published five beautiful editions that look at food around the world—often from the point of view of those who actually live in and are connected to those places—and has been putting out the excellent “Points of Origin” podcast more recently, which shows food and beverage in their full context, with episodes talking to Palestinian restaurateur Reem Assil, exploring natural wine, discussing indigenous foodways, and much more.

In this conversation, I wanted to specifically understand what led to his founding Whetstone and discuss the void that still exists in most food media, which fails to connect agriculture, justice, and joy to depict the food system in its fullness, without ignoring the cultural meanings of what we eat. Listen or read, then check out the podcast and follow him on social media, where his insights and poetry and cooking are always a bright spot.

Alicia: So, one, thank you so much for taking the time out to have a conversation with me for this newsletter.

Stephen: My pleasure.

Alicia: Can you tell me about where you grew up and what you ate.

Stephen: I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, and I ate regional food, fast food, and food from boxes. My father and my maternal grandmother are and were, respectively, really excellent regional cooks, so my whole repertoire of Southern dishes, southeastern dishes, I guess, is really strong; I grew up eating excellent versions of things like fried catfish, fried chicken, cornbread, macaroni and cheese, coleslaw, braised greens, cakes—stuff like that.

But also, you know, I was a baby with a very, very working-class mom and dad, and we ate at drive-throughs, we ate Pop-Tarts, and, in elementary school, we ate Lunchables. It was like a confluence of all those things.

Alicia: And how did you end up working in food, and specifically in food media?

It's the only industry I've ever worked—I guess media second, but prior to media, I had only worked in food. My first real job, I was 15 and I worked at an ice cream shop for my summer job, scooping ice cream, and then the summer after that, I worked at a pretzel shop. And then when I went to college, my freshman year, I was at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon, and I had to get a job. I was working at a little café there, a vegetarian café that also had a little wine retail situation.

I ended up dropping out of college, sticking with that job, going to culinary school, and kind of transitioning my whole life. But I always loved food. I would say, like, starting in high school. For instance, when I was a senior in high school, I would skip school, smoke weed with my friends, watch Julia Child, or read one of their books, and do wild shit like make soufflés. I vividly remember our idea of a good time was cooking and, when we could afford it, eating out at nice restaurants in Atlanta. It was always, even as a teenager, part of the theater of my life and entertainment and truth.

After college—I mean, honestly, I couldn't afford to stay in college, is what happened. And I was like, for one year of college I could go to culinary school, and I already know I love food and I can make a career out of it. So I dropped out of college my freshman year, went to culinary school in Portland, studied hospitality and restaurant management. Lived in a 400-square-foot, $500 a month apartment next to a methadone clinic, two blocks away from my culinary school, worked two jobs, and interned or staged at a kitchen in a country club. So I was just constantly working, constantly immersing myself in all things eating and drinking.

When I was 20, as part of that curriculum, we took a wine appreciation class, like an introduction to wine class, and I really, really got deeply into wine as a young person. I became a sommelier at 21 and that really unlocked a big worldview in my life, in terms of provenance and agriculture and the relationship of agriculture and provenance to our culture, society, and just who we are fundamentally as humans.

Alicia: I feel like that's so clear in Whetstone, both in the magazine and in the “Points of Origin” podcast, this recognition of these relationships between what we consume and what it means and where it comes from. Why did you launch Whetstone the magazine? What kind of void did you see in food writing or in food media that led to its creation?

Stephen: It's funny, I thought you were gonna ask me that. My original Kickstarter, from 2016, for Whetstone. It was a failed campaign; we raised $17,000 out of $50,000. Where it was then is actually where it is now and I'm actually quite proud of how on target we are with the original vision. I'm paraphrasing the language, but it basically says, you know, we're in the midst of a global food revolution, but the media is only talking about the chefs. There's no mention of origin, there's no mention of farmers or agriculture. This is a massive void. Someone needs to fill the void. This is our vision for Whetstone, and really talking about origin as an opening for much more profound belief systems around environment, around racial justice, around, you know, building empathy. So, I think we've always looked through origin as the prism, especially food origin, as the prism, as the most meaningful way to engage with other humans, and to just engage with food.

Alicia: By 2016, people would say that the farm-to-table movement had taken off and that farmers’ markets were huge, you know, at least in various urban and suburban areas; that they were a big discussion point in the food world. But how was that conversation that was already happening, how was it lacking to you?

Stephen: It was massively lacking and I feel and felt really qualified to speak on that movement that you're talking about, because I was working in the midst of it in San Francisco as a manager at Nopa restaurant, which is part of a lineage of the so-called farm-to-table movement as understood by the gospel of Alice Waters and disciples.

I feel that the beginnings of that movement, sort of, back to the land, started off pretty purely and earnestly when you look at what was happening in the country socially at the time. The impulse to want to go back to the land and say fuck it all, let it burn was very understandable; I think we're in that moment again. But like all good things, it becomes co-opted and foremost, it becomes co-opted by power and privilege. It's usually a soft cooptation, at the beginning. And what I mean by that is a movement that is ideologically earnest about wanting to return to nature is pretty wholesome, but it does ignore those folks who have the ability and the privilege to return to nature, who is welcome in nature, and also who is able to afford to build a life to acquire a home to develop a home in nature.

The same structural inequality that we talk about today of course existed three decades ago, four decades ago. So, the kinds of communities and the kinds of ideologies that are reverberated by these communities end up being just as harmful and just as damaging as the more overt forms of racism and exclusion, because it only ends up serving a small population of people who are connected through their own social identity—who are connected through their race, who are connected through their privilege, their access to power. And so while these people are in areas like Sonoma County and Napa, Alice Waters who herself had come from money had the privilege of traveling around Europe—these are possibilities for you to talk about an idealized world of returning to nature, eating locally, and, in that message, you know, food justice, food access is completely obliterated, and the opportunity for her to bring her disciples, from that same power and same joy that she experienced, the exhilaration of living on the land, eating on the land, being on the land totally ignores and undermines the fact that that privilege is not available to most. And so, to exalt that lifestyle without being honest about that joy and exhilaration and access not being equally available is disingenuous. And of course that is reflected in the media, and the composition of the news organizations who are covering these chefs, who are perpetuating their message, that are leading this crucial point.

Basically what it looked like from me being both a part of the disciples, as a manager at a farm-to-table restaurant that was a descendant of Chez Panisse, and I covered it exhaustively: I mean, really the precursor to Whetstone was a project called Nopalize, that I to help our diners more deeply connect to the people who were growing their food, because there was a major disconnect. The ideology of what we were talking about at lineup and tasting—this is the farmer, it comes from this. I'd be like, Can anyone point out Yolo County on a map. They’re like, no. They're memorizing all the names and farms, all the names and the different entities and I'm like dude, you have no—there's still no relationship, really, to the land, there's no relationship to the politics of the land, there's no relationship to the people who are committed and the sacrifices of growing on the land. So, you know, I started kind of an in-house media company that was really committed to bringing people on trips, but also, you know, in content being made to try to close that gap. So I've always, you know, I guess in my own way been a product of trying to bridge social justice and food justice with my almost innate education around fine dining and hospitality standards.

Alicia: I've been thinking about this a lot, how—I mean, I'm always thinking about this a lot—but people view, you know, this disconnect between farmers and the land and not recognizing those connections... They don't view that as a justice issue, they don't view these things as connected to justice or to politics. They view these things as snobbery. How do you have the conversation? And I think you're very good at this, and I think Whetstone is good at this, and the podcast is good at this, at presenting these things, not as a point of elitism, but as a point of culture. How do you bridge those gaps and how do you think more writers or more people creating media can, you know, talk about where things come from and why that's important, without alienating people, and also why does it alienate people to talk about where food comes from? I think that was three questions.

Stephen: I think that it is alienating because it's frightening. The truth is very confrontational, and in the truth, people are implicated, and who wants to be implicated?

When you start talking about power and privilege, it completely sullies what you think is a pristine, liberal worldview of having a garden and living on the land, like excuse you talking to me about access issues and urban communities, you know, like no one wants to go there. But the problem is, the analysis completely falls apart from a justice perspective, the analysis falls apart if you ask the question, do you believe everyone has equal access to food? And if they say yes, it immediately undermines everything that they're purporting because what they should be purporting is actually equitable access to the same quality of food that they eat but that's not what they're purporting, that’s not the culture that the media—that's not the message that gets through. And so we end up talking about like, whatever, the fucking egg spoon and whatever clips come from people like Alice Waters, and lost in all of that is like a—I mean, this isn’t a critique, I don't mean to critique her, I actually love Chez Panisse; I think of it as more of an institution. And honestly this woman is in her mid-70s and I don't feel comfortable really going that hard, you know. It’s not about her but because in a way her name and her legacy have become synonymous, because it is a really kind of clarifying example of the disassociation between the ideals of the farm-to-table movement and actually what's lacking in practice.

And then around the question of origin, you know, we have been saying from day one that there's so much power in origin. We've been trying to shift our readership and other people in the media to think more critically about origin, because we feel like that is where our power lies and that gives us so much range to talk about food from a perspective of gastronomy and dining and pleasure and enjoyment, because we are connected to that history, just in the same way we're connected to the history that understands the politics of land, and in understanding land and agriculture that means that we understand that there has always been a disenfranchised class and always a ruling class associated with that land. Prior to that there were many different indigenous tribes, even precolonial, there's still, you know, intertribal politics, around land, you know, there's no dissociation.

So for us, because, again, we kind of have this origin filter allows us to give the same berth, the same energy, the same scope when we're, you know, speaking in more I guess overtly political tones, or on subjects like natural wine or fine dining restaurants that might otherwise go out of context, without editors, people like Layla [Schlack], who helps us with a kind of editorial vision, making sure that we're consistent in our analysis and sharing the full spectrum of experience.

And we think our connection to history and our appreciation for history allows us to do that better, and we think that if more people in the media did that food media on the whole would be a lot better. You’re really good at it. That's why people are paying attention to your work, because it holds the same analysis, which is that, yes, you can talk about how to properly make a drink, you can talk about proper bar etiquette and culture from the service side, from the consumer side, and obviously your entire platform being centered around veganism is intensely powerful for people, because it doesn't let you or anyone else off the hook in the analysis; they can't just show up for the, you know, Negroni commentary without understanding the connection to the food system as well. And that's the same system that we should all operate in.

Alicia: I would hope the current moment is forcing people to make better considerations. I hope. I hold little hope. But one of the things that I think Whetstone is so good at versus other magazines is being global. And so I wanted to ask how you achieve that and why that was a goal, as well. You know, to really have people from different places around the world writing about their own land, their own cultures, their own foods. Because you know, so many magazines act as if that is an impossibility to do, and you prove that it's not. But how did you go about achieving that?

Stephen: Well, we really wanted to do that, that’s something else that was in that original language and vision as well. Because the same kind of accountability that we're speaking on—I mean, we have a long way to go. I'm not saying that we have, by any means, arrived. Believe me, I'm poking more holes than anyone else on the work that we're making. But it didn't feel consistent for us to talk about food as part of a larger global human history and then have it be like focused on New York, the Bay Area, and a couple of cities in between. So we had to commit to a global platform and a global message to begin with, because we were already kind of on that, again, just in our connection to the kinds of stories that we were wanting to tell. So, more like, you know, I guess, behind the scenes what happened is we, you know, the first edition that we made, we reached out to people in different parts of the world that either we already had a relationship with or in some cases had just traveled there, and we created kind of stylistic standard and aesthetic for Whetstone, what we were trying to make in form but also in content.

And I think that once people saw the first edition of Whetstone, it became really evident what was missing and it kind of proved what our promise of being different would look like in real life. And I think more than like the public per se, the biggest, the most like enthusiastic response that we got was from other creative people who really appreciated the work that we put into sourcing and placing the photographs, who appreciated the original artwork that we commissioned, and really just like holding art at a really high standard alongside our messaging and alongside the content. So, once we created that first edition, slowly but surely we have been the beneficiary of mostly inbound pitches from people in other parts of the world, usually accompanied with a message that says, I'm so glad you exist. Like, I've been wanting to place this article, but I haven't found a magazine that would make it make sense. It's just like, people are expressing what we were feeling from the very beginning, you know, when we publish people in Iran or in Palestine in a way that doesn't make them feel tokenized but like part of a larger global fabric, that's what we were trying to do from the beginning. And I think people who recognize that, especially people who are holding stories that are dear to them, have offered us that that trust as we continue to grow and publish more people.

Alicia: I'm gonna ask you my final question. For you, is cooking a political act, and if so, in what ways?

Stephen: I mean, duh. Deeply. Of course. It's been a huge shift for me because the first couple of years of getting Whetstone off the ground, I had to spend so much time on the road meeting with contributors, speaking, selling the magazine, on and on. And so this is the most that I really have slowed down and been idle in, you know, years, and it's been so highly activating for me like, politically, because immediately, as I'm in Atlanta, I'm like connected to this amazing network of Black farmers who are growing food on rooftops, are growing food on the west side of Atlanta. I'm like, man, we have produce that tastes like it was grown in California out here being grown by beautiful Black women whose skin is, like, glistening, growing the best kale I’ve ever seen in my life. I'm like, this is fucking glorious, you know, like this is the politics of food; this is almost the vision of food system that I hope for, where restaurants are thinking about how to serve frontline workers in medicine, you know, they're thinking about—I mean, not all of them, but like the beacons that we're talking about. They're looking at how they can serve as food hubs in a completely different way than just, you know, serving multi-course tasting menus that no one can afford and that have gentrified neighborhoods.

You know, so like, everyone who's cooking at home right now who’s making supply chains more cumbersome. Everyone who listened to “The Daily” and heard a gross story about you know what's happening at the meat facilities, like, and they don't want to buy meat, like that is very political whether or not they are aware of the politics of that decision to not purchase based on the media that they consumed. Whether or not people are conscious of their eating or cooking being a political act, it's always that; it's always a vote for a more corporate food system, a more industrialized food system, a more harmful system, or it’s the opposite. And I don't mean to assign any moral judgment around that, because so much has been done to make a completely morally pure purchase impossible, but I'm just saying more matter of factly that, you know, every time we buy food, it's either one of those things or the other things. So, cooking for me has really centered the part of it that is political and a lot more deeply connected to Black folks growing food in Atlanta, and like, that's a community that really matters to me, that I'm happy to be back in touch with, and that would have never happened—or not never happened but I’m kind of in Atlanta unexpectedly cooking when I would have been God knows where. So I do feel really, like, politically connected in a way that I haven’t in a long time.

Alicia: Wonderful. Well, thank you so much for chatting with me.

A Conversation with Stephen Satterfield